In 1938, in a small town in Upper Austria, one of the many Nazi concentration camps was constructed. It was known as the Mauthausen concentration camp. It existed from 1938 to 1945. The camp was run and guarded by the SS. The people who were imprisoned here came from many countries in Europe: Poland, Russia, France, Italy, Germany, Austria and others. They were political opponents, belonged to marginalised groups (e.g. ‘criminals’, ‘asocials’) or were persecuted for anti-Semitic and racist reasons (e.g. Jews). Most of the prisoners were men, but there were also women and children. In the Mauthausen quarry, the prisoners carried out hard forced labour.

In the more than 40 subcamps (Gusen, Steyr, Linz, Ebensee, Vienna ...), they were deployed in the arms industry. People lived in overcrowded accommodation. They were not given enough food and clothing, and they starved and died of diseases. SS men beat many prisoners to death, shot them or murdered them in the gas chamber at Mauthausen. In total, almost 200,000 people were imprisoned at Mauthausen and its subcamps. Half of them lost their lives.

The Mauthausen concentration camp was on a hill and could be seen for miles around. Many people were involved with the camp: they worked there, brought deliveries or knew SS men. Almost everyone knew about the death camp. Often, the SS men committed the crimes in full view of the population. On 5 May 1945, the Mauthausen concentration camp was liberated by US troops.

Here you will read the story of a person who was connected with the Mauthausen concentration camp.

Franz Jäger

Text: Evelyn Steinthaler – Illustration: Johannes Doppler

In September 1944, the ‘Volkssturm’ (home guard) is formed in Nazi Germany. All able-bodied men between 16 and 60 years of age who have not been drafted into the Wehrmacht must report to the Volkssturm. The Volkssturm is deployed to defend ‘home territory’ and is intended to serve the ‘ultimate victory’ of the German Reich. Men in the Volkssturm do not receive military training like the soldiers of the Wehrmacht. They are also not given a uniform. They can only be identified via an armband which reads: ‘German Volkssturm – Wehrmacht’. Their tasks include construction work and securing and defending towns and villages.

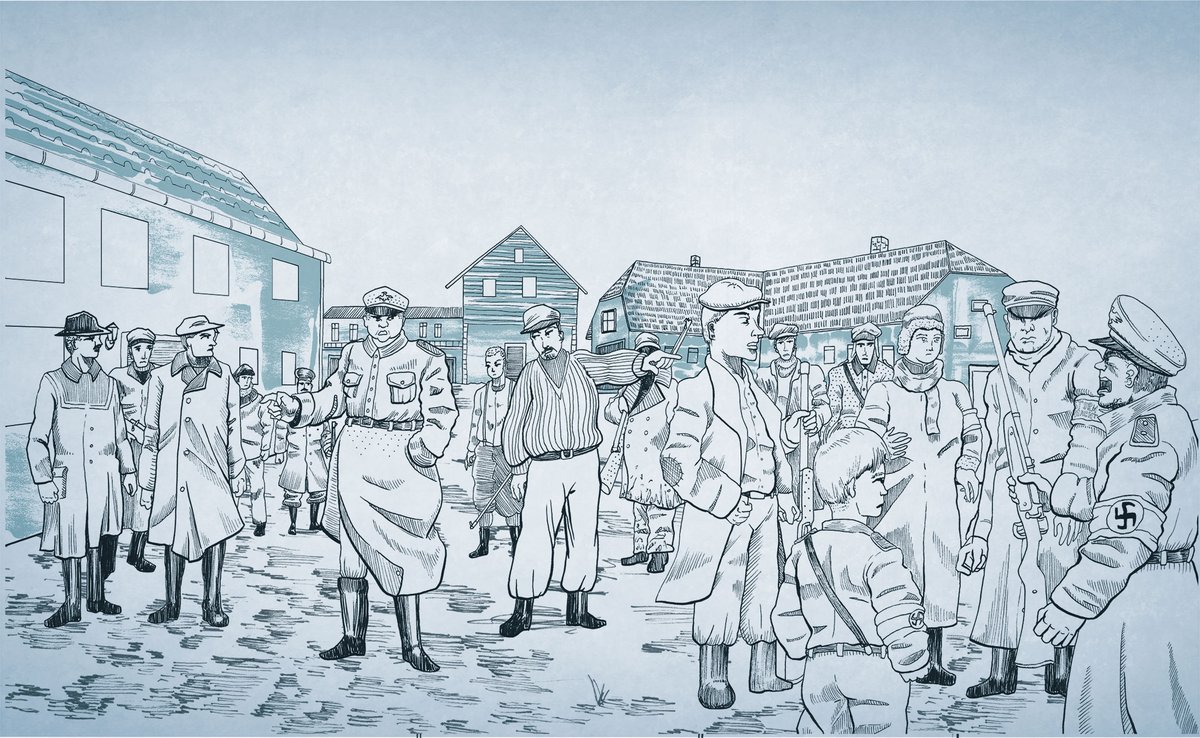

Franz Jäger from Hagenberg in the Mühlviertel region is a member of the Volkssturm. He lives in Schwertberg and is 44 years old. He makes slippers for a living and has been married since 1940. Early in the morning of 2 February 1945, he is woken up by the head of the fire brigade, Mr Hoffmann: Franz Jäger has to join the local Volkssturm in their search for Soviet prisoners of war. They are to search for Soviet prisoners of war who have escaped from Block 20 of the Mauthausen concentration camp only a few hours earlier. Over 500 were involved in the escape attempt and about 100 were shot during a fight at the camp wall. But over 400 POWs managed to escape. Jäger was out drinking the night before and didn’t get home until four in the morning. He refuses to join. But at six o’clock, the head of the local farmers’ association, Karl Glinsner, calls on him to join the search for the escaped concentration camp prisoners. The camp leadership at Mauthausen under Franz Ziereis has called for a ‘hare hunt’ for these men, who have been driven by desperation to escape certain death in the concentration camp. In an announcement at the market square, Norbert Niedermayr, the Volkssturm commandant in Schwertberg, describes them as ‘dangerous fugitives’ who ‘must all be shot’.

D

Almost all the escaped concentration camp prisoners are members of the Red Army. Following escape attempts and acts of resistance, they have been brought to Mauthausen as ‘K prisoners’ to be murdered in the camp. They are not ordinary soldiers, but officers and senior non-commissioned officers.

In addition to the Volkssturm, the SS, SA, gendarmerie, Wehrmacht, fire brigade and Hitler Youth are called upon to hunt down and kill the escapees. But civilians also join the ‘hare hunt’ and shoot at the prisoners who have escaped with their own private weapons without receiving orders.

Early that morning, Franz Jäger is ordered to Theresia Luegmayr’s farm as reinforcement. As soon as he arrives, he threatens to shoot escapees. Prisoners are already being shot on the surrounding farms. Jäger searches the hayloft together with Josef Bernhard, who has also been ordered to come.

They find an escaped prisoner hidden in the hay. Jäger first tries to get Bernhard to shoot the man in the hay, but Bernhard refuses. As Bernhard turns away, Franz Jäger shoots the man lying on the ground in the forehead. The prisoner of war shot by Jäger is one of more than 400 who are murdered in the ‘Mühlviertel Hare Hunt’. Only eight escapees are known to have survived – for example, because they were hidden by families on farms in the surrounding area.

In the years following the Second World War, ‘hare hunt’ perpetrators are tried before Soviet military courts and Austrian people’s courts for war crimes. In June 1946, charges are also filed against Franz Jäger at the gendarmerie in Schwertberg. The trial takes place at the Vienna People’s Court. ‘The defendant admits to firing the shot but pleads self-defence,’ the court transcript reads. Jäger’s claim that the escaped concentration camp inmate threatened him with an iron rod is not deemed credible by the court. Nor does the court see the fact that he was still intoxicated from drinking the previous night as a mitigating circumstance. In 1948, the People’s Court sentences Franz Jäger to twelve years of imprisonment with hard labour. He initially serves his sentence in the Stein an der Donau prison.

Seven other perpetrators receive long prison sentences from the People’s Courts, while Schwertberg Volkssturm commandant Niedermayr, who is charged with ‘issuing criminal orders,’ is acquitted after contradictory witness statements. At the beginning of the 1950s, the convicted perpetrators of the ‘Mühlviertel Hare Hunt’ are released early.

In 1953, the Austrian Minister of the Interior, Oskar Helmer, sends a letter to the Minister of Justice, Josef Gerö. Attached to the letter is a list of twenty people recommended for pardon during the Christmas period. Franz Jäger is on this list. ‘His offence is purely a military order offence, which he was guilty of as a member of the Volkssturm,’ Helmer says. Franz Jäger is pardoned and released from prison on 18 December 1953.

He returns to Schwertberg, where he lives until 1957. Franz Jäger then moves to Steyr and lives there until his death in 1972.

- 1900 Franz Jäger is born in Hagenberg

- 1914 28 July – Start of the First World War

- 1918 11 November – End of the First World War

- 1933 30 January – Adolf Hitler becomes Reich Chancellor in Germany

- 1938 12 March – ‘Anschluss’ (‘Annexation’) of Austria to Nazi Germany

- 1938 8 August – Construction begins on the Mauthausen concentration camp

- 1939 1 September – Start of the Second World War

- 1944 Conscription to the Volkssturm

- 1945 2 February – Soviet K prisoners escape from Block 20 of the Mauthausen concentration camp; the ‘Mühlviertel Hare Hunt’ begins

- 1945 2 February – Franz Jäger shoots an escaped K prisoner during the ‘Mühlviertel Hare Hunt’

- 1945 5 May – The Mauthausen concentration camp is liberated by the US Army

- 1945 8 May – Nazi Germany surrenders; end of the Second World War in Europe

- 1946 Charges brought against Franz Jäger

- 1948 The Vienna People’s Court sentences Franz Jäger to twelve years in prison

- 1953 Minister of Interior Oskar Helmer proposes pardoning several convicted felons, including Franz Jäger

- 1953 He is released from prison

- 1972 Franz Jäger dies in Steyr

Further reflection in groups...

What do you learn in the account of the ‘Mühlviertel Hare Hunt’ about how people behave towards escaped prisoners?

Franz Jäger is pardoned in 1953 because he ‘only’ acted on orders. Who do you think is responsible for a criminal act: The person who gives the order? The person who carries out the order? Or both?

At the time, many people saw the escaped K prisoners as enemies. What is your impression of how people who have escaped are reported and talked about today?

Ask your guide at the beginning of the tour at the Mauthausen Memorial if you can visit the area around what used to be Block 20.